San Ysidro has an air-pollution problem.

The small, predominantly low-income and Latino community is perched at the world’s busiest land border crossing – and all that border traffic is causing some problems.

In 2017, roughly 13.8 million passenger vehicles and more than 33,000 buses crossed throughthe San Ysidro Port of Entry. Many of those vehicles sat in traffic near the border for anywhere from 15 minutes to two hours, idling exhaust into the immediate area all the while.

With an expansion of the Port of Entry underway, local nonprofit Casa Familiar decided two years ago to monitor the area’s air quality. Initial findings suggest poor air quality in the community is linked to the Port of Entry.

It’s not the first study showing the environmental impact of cars idling as they wait to cross the international border. It’s not even the first one that’s been done in San Ysidro, though it may end up being one of the most comprehensive.

Yet, there’s been little done to mitigate environmental issues in border communities.

“We needed this data to not only ask, ‘Do they have to mitigate?’ but to try to hold them accountable for lower border wait times, which is what they said the expansion would do,” said David Flores, the community development director of Casa Familiar.

There’s little doubt that cars backing up at border crossings is bad for the people who live nearby.

Previous studies have shown that border agents in El Paso were exposed to higher-than-recommended carbon monoxide levels, that San Ysidro’s asthma rate is 18 percent higher than the county as a whole, that 41 percent of San Ysidro residents live within 500 feet of a pollution source and that border traffic hurts San Ysidro’s air quality, and that air pollutants are elevated near the Calexico border crossing. And a 2016 study of studies on emissions near border crossings found a general consensus that air quality is poor near border crossings, mostly harming pedestrians and people who live nearby.

Now, Casa Familiar, along with partner organizations including CalEPA and the Schools of Public Health at the University of Washington and San Diego State University, has set up air monitorsthroughout San Ysidro. They’re comparing the results to data from the Tijuana estuary, Tijuana and at the Donovan State Prison in Otay.

There are several data points in the initial findings that indicate that particulate matter concentration – air pollution – is linked to traffic through the Port of Entry.

Specifically, a monitor in Tijuana placed right near the Mexican side of the Port of Entry saw spikes in particulate matter when commuters who live in Tijuana but work in San Diego sit in traffic crossing the border. Pedestrian commuters during that time may be facing impacts from the air quality as they wait to cross, standing next to idling cars.

Graph courtesy of Casa Familiar, San Diego State University and University of Washington

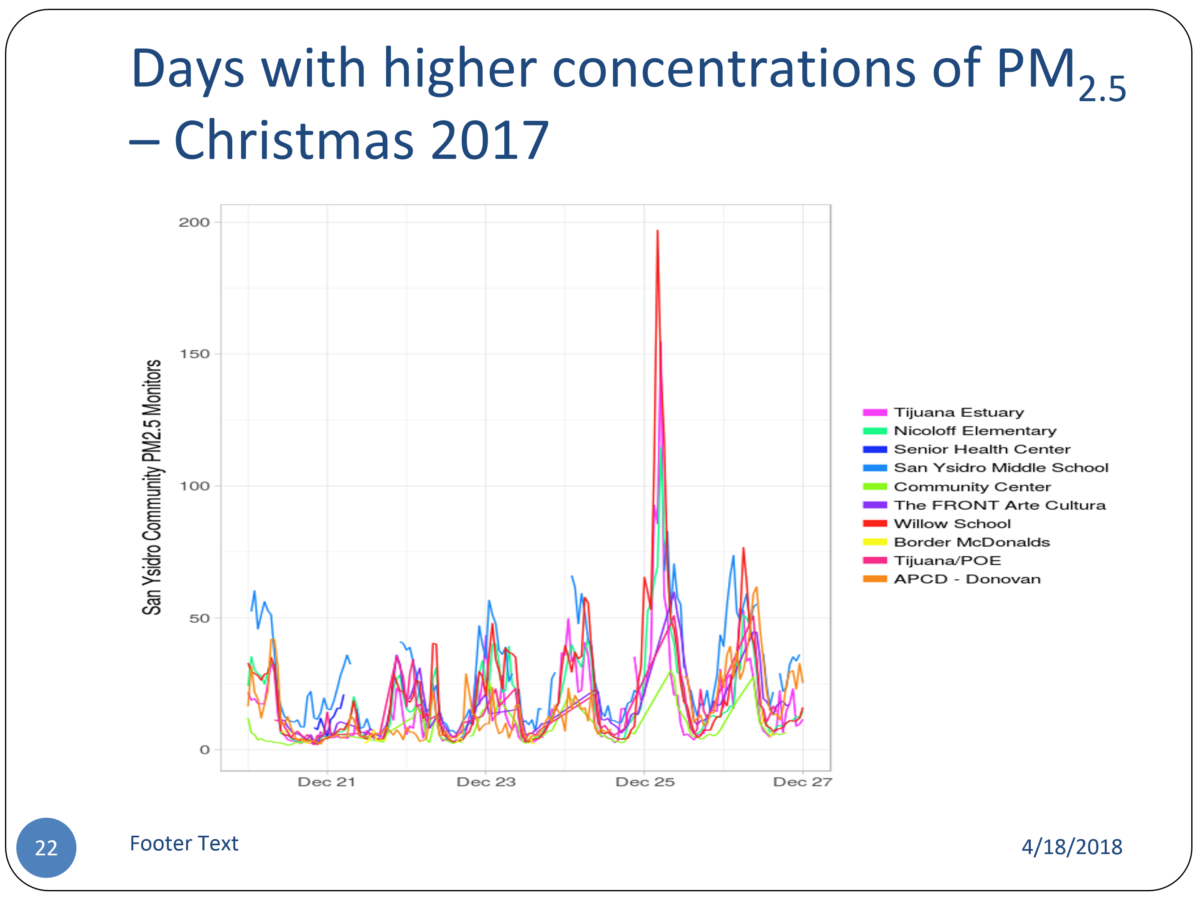

The numbers also spike on days when traffic increases, like Christmas.

Graph courtesy of Casa Familiar, San Diego State University and University of Washington

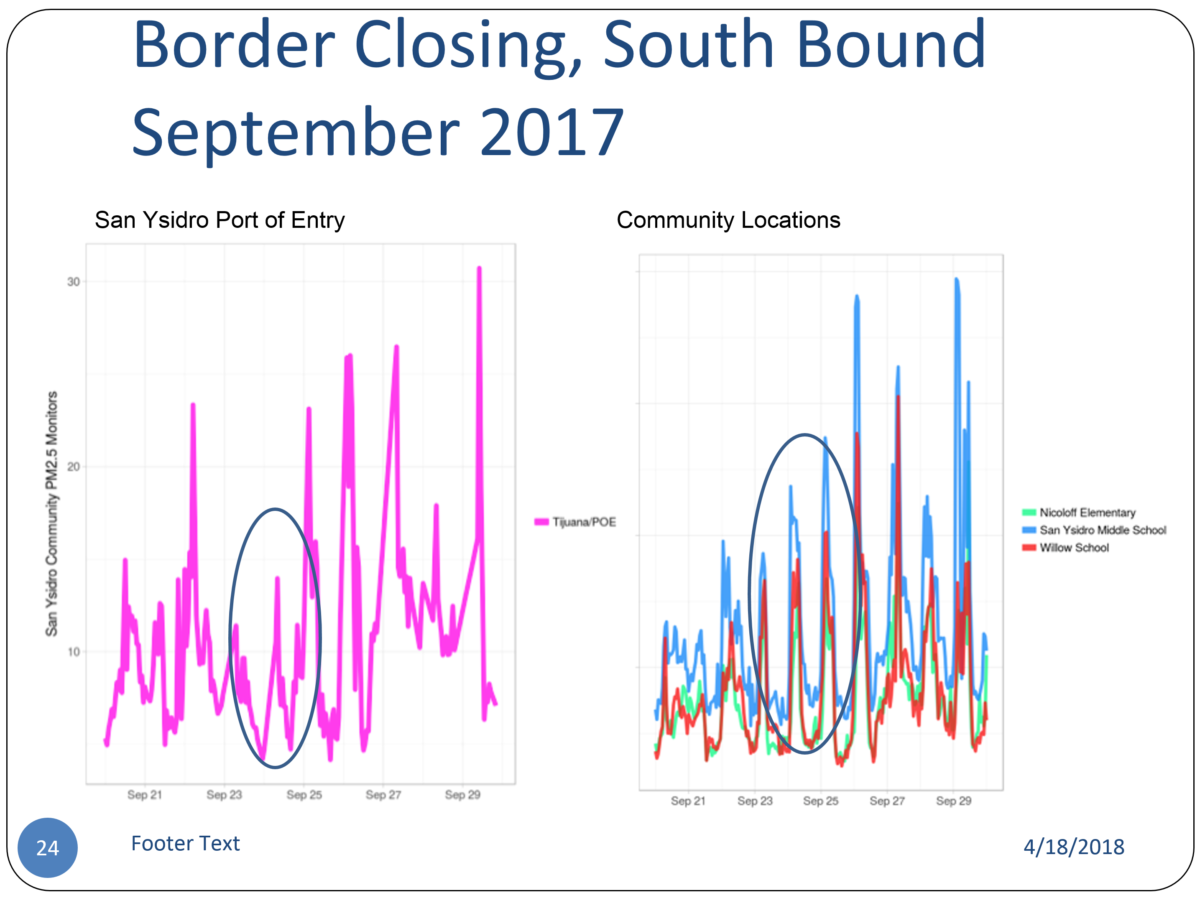

Finally, the monitors also measured a three-day period last September when the Port of Entry was closed. Particulate matter dropped.

Graph courtesy of Casa Familiar, San Diego State University and University of Washington.

The Port of Entry expansion is supposed to speed up northbound border crossings, and construction on the Mexican side is supposed to do the same. The federal government expects border waits to drop even while traffic increases, according to environmental and traffic studies for the project.

That’s why, despite the accumulation the environmental review for the Port of Entry expansion found the expansion would cause “no impact related to environmental health and safety risks to children.” It goes even further, saying that without an expansion, increased congestion would lead to environmental justice issues in the community.

“Cross-border travel is forecasted to continue to grow due to projected local and regional growth, and border delays are expected to increase correspondingly, placing a strain on existing border facilities and infrastructure at the San Ysidro [Land Port of Entry],” reads the report.

The report estimates that without the expansion, maximum wait times would exceed three hours during the commuter peak period by the year 2024, and 10 hours by 2030.

Groups representing San Ysidro residents have been trying to find ways to ensure the federal government can mitigate the environmental impacts of the expansion.

As far back as 2009, groups including Casa Familiar, the San Diego Regional Chamber of Commerce, the San Ysidro Planning Group, the San Ysidro Business Association brought up environmental justice and air quality issues relating to traffic.

Jason Wells, CEO of the San Ysidro Chamber of Commerce, said the community has won some concessions as part of the project. For instance, he said, the chamber and others got additional pedestrian routes going both north and south by reminding officials of the project’s local impact.

“We intervened and were able to get the dual pedestrian crossing,” Wells said. “That helps the environment, and it helps San Ysidro local businesses. People who drive through don’t stop here.”

Wells said changes in how buses are inspected will also help, by encouraging more people to take buses rather than drive down alone or in smaller groups in passenger vehicles.

There are also plans for mass transit hubs on both sides of the border, which Wells says he hopes encourages more people to cross by foot, rather than by car. Though those plans – especially on the Tijuana side – have been slow to materialize.

A 2016 Commission for Environmental Cooperation study also laid out some solutions that have helped. Trusted traveler programs, like SENTRI, which allows pre-screened participants and their vehicles to cross more easily have helped with wait times and idling cars. A pilot program several years ago at the Otay Mesa border crossing retrofit Mexican heavy-duty diesel engines to help reduce diesel emissions, which are a big source of smog and other air pollutants.

The Port of Entry isn’t the only thing causing environmental problems for San Ysidro. Another curious outcome of the study so far is that black carbon levels spike seasonally – in spring and fall – and at night. This is happening both in San Ysidro and further west in the Tijuana Estuary.

Flores says the spike could be from multiple things, probably stemming from Tijuana, where air pollution from heavy traffic, trash burning and other things may be crossing the border and getting trapped in border communities like San Ysidro, which are in valleys.

Unfortunately no physical border infrastructure can really stop that.

That’s why one of the next steps for the group will be to put more air monitors in Tijuana, he said.