Hans Backhoff, CEO of the Monte Xanic winery in Valle Guadelupe, is standing in the facility’s elegant tasting room, ticking off stats about Mexico and wine drinkers.

“Mexicans drink 800 milliliters per year per capita, the U.S., 9 liters and Argentina, 15-20 liters,” Backhoff said.

Mexico, the home of cerveza and tequila, is a bit player in the global wine market. But domestic producers harbor mighty aspirations, especially in the starkly beautiful Valle Guadalupe, a Northern Baja desert region responsible for 85% of the country’s wine production.

“There is a big change happening in the market,” said Backhoff. He said Monte Xanic sold 60,000 cases last year and expects to sell 75,000 cases in 2017, with the bulk of sales inside Mexico. The long-term sales goal is 150,000 cases.

“We have a good problem,» Backhoff said. «Mexicans are drinking lot of wine.”

Oregon wine producers are paying attention. Mexico accounts for only 1% of Oregon wine exports, but the potential market is growing, said Margaret Bray, international marketing manager for the Oregon Wine Board.

This past year, OWB was awarded an Emerging Markets Programs grant specifically for Mexico. EMP grants help U.S. organizations promote agricultural products to countries that have, or are developing, consumer-oriented economies. OWB used the funds to host a series of seminars in Mexico City and Cabos in May.

“In tourist areas like Baja and the Yucatan, there is a real possibility for genuine sales of expensive wine,” said David Adelsheim, chairman of Adelsheim Vineyard in Newberg.

Adelsheim said he exports 20-30 cases annually to a Mexican importer, who sells most of the cache in Baja and Yucatan. The majority of imbibers, Adelsheim said, are American tourists.

***

Baja’s burgeoning wine industry is part of a boom in Mexican gastronomy fueled by tourism and an expanding Mexican middle class. Although many Americans still view Mexico as an impoverished nation ruled by a wealthy elite, the ranks of middle class Mexicans are growing.

«Actually, the income gap in Mexico is getting smaller,» said Roberto Dondisch, Washington state’s Mexican consul general. «Not by much, but it’s shrinking.»

The Baja wine region, marketed aggressively by tourism officials and featured this past year in Conde Nast Traveler and the New York Times, spotlights the close if complex relationship between Mexico and the United States. Even in the Trump era, businesses in both countries are pressing forward with open border partnerships and not only in the tourism sector.

“Business trumps politics,” said David Mayagoitia, president of the board of economic and industrial development corporation of Tijuana.

Mayagoitia spoke during a presentation in Tijuana about a new medical tourism complex, New City Medical Plaza. The facility, which is under construction and will include a hotel, restaurants and surgical center, targets Americans seeking cheaper health care.

In the past three years, medical tourism to Tijuana has increased 30%, said Isaac Abadi, chief executive for the new project.

“People come for dental work, but when they see the professionalism of other doctors they feel safe for other procedures,” Abadi said.

A new bi-national hospital is expected to boost confidence further, he said. The Mexican health insurer SIMSA and Scripps Health in San Diego are partnering on a new hospital in Tijuana. Scripps is consulting on the hospital’s planning, construction and operation, and the hospital will be branded as an affiliate of Scripps.

Uncertainty around American health care policy could provide another boost, said William Braun, a Portland attorney who handles medical tourism cases. “If there is no individual mandate, that could lead to increase in medical tourism,” Braun said.

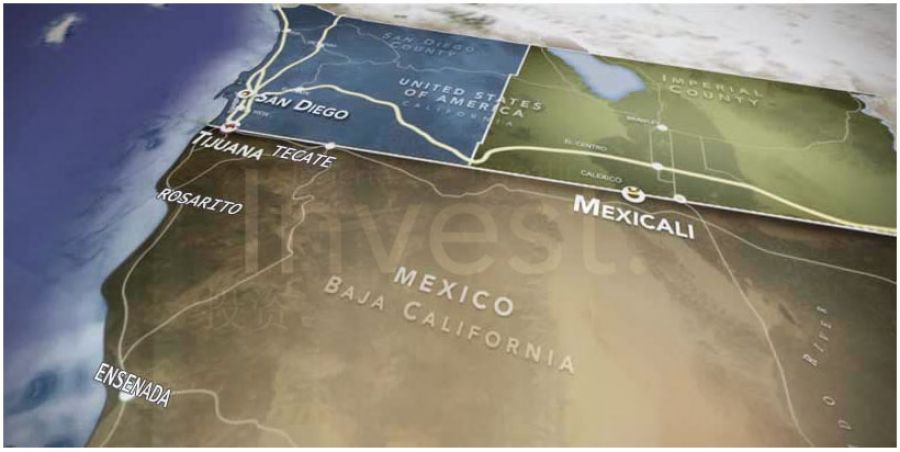

Baja’s medical tourism sector provides grist for the «Cali-Baja” mega region, a cross-border economic zone that spans San Diego County, Imperial County and Baja California.

A potent Cali-Baja symbol is the Cross Border Xpress, a privately-funded pedestrian walkway and building that connects San Diego directly to the Tijuana International Airport. The antithesis of a wall, Cross Border Xpress expedites travel for the approximately 2.4 million passengers who often face hours long waits at the congested border crossings in San Ysidro and Otay Mesa.

Oregon officials recently celebrated another expedited crossing between the U.S. and Mexico: a new direct flight from Portland to Mexico City, starting December 1, 2017.

More than 22,000 visitors from Mexico came to Oregon in 2016, and the majority were corporate travelers, said Linea Gagliano, global communications director for Travel Oregon, the state tourism commission.

“We hope the new flight will help keep everything open and make it easier for Mexicans to come,” Gagliano said. “They are welcome here.”

The number of Mexican visitors to Oregon increased by 115% this year, the biggest increase from any country, Gagliano said. (China clocked in with the second largest increase in visitors: 85%.)

As borderless initiatives advance, Mexican civic and business leaders battle what many describe as their biggest challenge: the perception that Mexico, Tijuana in particular, is a dangerous and crime-ridden place to visit.

Although Tijuana homicides declined for a period, the border metropolis saw a steady rise in killings in 2016, according to an annual report released this past spring by the University of San Diego’s Justice in Mexico program.

“I’m pressing to do something about the drug violence,” said Ivette Casillas, a Tijuana councilwoman who attended the medical tourism discussion.

During a presentation held at Tijuana’s sleek new Culinary Art School, Baja tourism officials touted a steady rise in foreign visitations. The upbeat discussion was challenged by Rafael Fernandez, a former foreign policy advisor to former President Felipe Calderón and founder and chair of the School of International Studies at the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM) Mexico.

“Why don’t you talk about the challenges, the insecurity in Tijuana?” Fernandez asked.

Entrepreneurs are unfazed.

Javier Gonzalez, the Culinary Art School’s founder, said the school trains chefs from Mexico and around the world. Gonzalez said a group from Oregon was planning a visit this month in advance of opening a Mexican restaurant in Portland.

At Monte Xanic, Backhoff is grappling with a different set of issues. He touted the winery’s commitment to environmentally-friendly viticulture and local workers, and said Valle Guadalupe is positioned as a community-based alternative to the mass tourism that dominates Cabo San Lucas and other Mexican beach resorts.

But, like Oregon wineries, Monte Xanic is fielding inquiries from large buyers in Europe and elsewhere eager to cash in on Valle Guadalupe’s success and unique terroir.

“Maintaining our independence and authenticity in the next 10 years will be very hard,” Backhoff said.