For 16 years, the international community has marked Dec. 18 as a day to celebrate the world’s immigrants. This year, the International Organization for Migration has asked that International Migrants Day also be considered a day of remembrance for those who have died or disappeared on their journeys in search of a better life. For Europe’s citizens, this tragedy is becoming all too common: Many have grown accustomed to daily reports of shipwrecks that have left bodies strewn across the Continent’s shores. The conditions facing the floods of people pouring into Europe are getting worse, and several EU member states have tried to shut their doors to outsiders. But in doing so they have brought the bloc, founded on the principle of open borders, even closer to its breaking point.

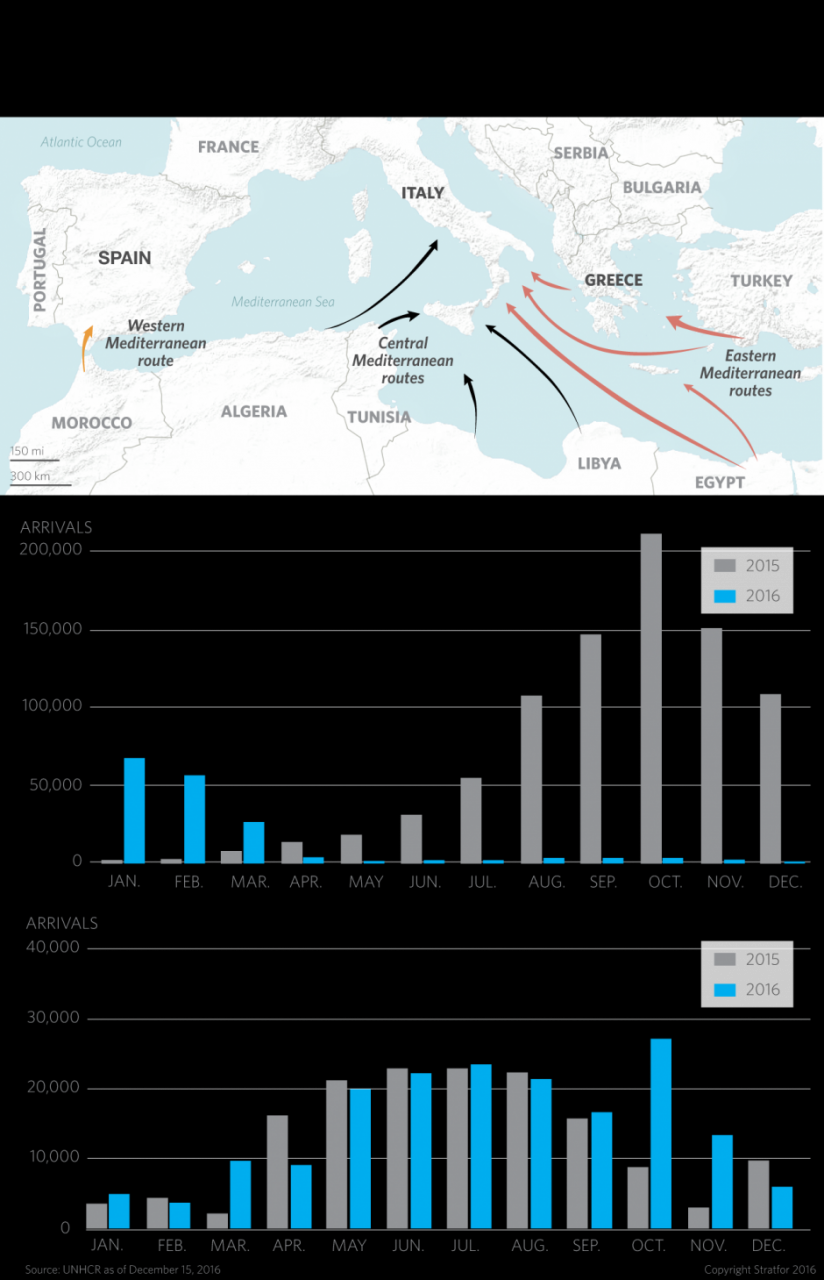

According to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, nearly 360,000 people have arrived in Italy, Greece and Spain by way of the Mediterranean this year. Though a far lower figure than that seen in 2015, when roughly a million migrants flocked to Europe’s border states, it is still a source of concern for European leaders. EU countries managed to stem the flow of people into their territories earlier this year by closing borders along the Balkan migration route and striking a deal with Turkey. Many of those border controls are still in place, disrupting the free movement of people and goods the European Union is based on.

The bloc’s agreement with Turkey may not be as enduring. European countries know that they need Turkey’s cooperation to curb the waves of migrants streaming across their borders, but they cannot seem to agree on what concessions they are willing to offer Ankara to get it. Turkey has demanded that the bloc liberalize visas for its citizens, but EU members are split on whether or not they should. Austria, which has been grappling with some of the strongest nationalist sentiments in Europe, has even argued that Brussels should suspend its negotiations with Turkey on its path to EU membership. The European Union, meanwhile, has tried to replicate its immigration deal with Turkey among several countries in Africa. But restricting African migration routes will continue to create challenges, especially since Libya — one of the primary transit states along the central Mediterranean route — has no stable government with which to partner.

As migrants continue to head to Europe’s southern coast in droves, different regions will offer different ideas about what to do with them. Southern European states such as Greece and Italy will focus on easing the logistical, political and economic burden of housing the crowds of people clamoring to cross their borders. Their neighbors in Northern Europe, on the other hand, will insist on adhering to the bloc’s long-standing immigration policy, which says that countries of arrival must register and house migrants. In return for Southern Europe’s cooperation, Northern Europe has pointed out that other EU states could take in limited quotas of migrants. But over the past year, it has become clear that this simply will not happen. Eastern European states, in particular, have steadfastly refused to agree to any EU program that redistributes migrants.

However, immigrants from Eastern Europe are causing consternation throughout the Continent as well. In fact, anti-immigration sentiments — largely directed against Eastern European laborers — were one of the biggest driving forces behind the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union. Though formal Brexit negotiations have not yet begun, the British government has already made it clear that its control over British migration policies is not negotiable. At the same time, the European Union has begun tightening the rules for distributing social welfare to European citizens who live in an EU state other than their home country. It has also started cracking down on the employment of «posted workers» — laborers from the bloc’s poorer countries who can be hired more cheaply than their counterparts in richer states. Because Eastern European citizens often benefit from both of these policies, member states in the region have vehemently opposed the impending restrictions.

To make matters worse, all of these changes are taking place in an atmosphere of growing political uncertainty. Public opinion is starting to lean in favor of Euroskeptic political parties that espouse nationalist policies, and at least three of the European Union’s founding members — France, Germany, the Netherlands and possibly Italy — are preparing to hold elections in 2017. In each of these countries, issues like immigration and security will be at the center of the debate, issues that populist parties have capitalized on to bolster their own anti-immigration agendas. In response, their mainstream competitors have shifted away from ideals of European integration in hopes of keeping their anti-establishment rivals from sapping up too much of their popular support.

So, the world’s migrants — regardless of whether they are seeking safety, asylum or economic opportunity — are gearing up for an even tougher year ahead as the Continent’s leaders try to reassure their constituents by slashing the benefits and hiking up deportations of non-citizens. And as the migrants’ outlook worsens, so will the prospects of the European bloc that is determined to keep them out, even if it comes at the expense of its own stability.