It’s only about 20 miles from Tijuana to San Diego, yet the distance between the two cities has sometimes seemed impassable over the centuries.

One reason for this is the perception that San Diego has historically looked down upon Tijuana as a “Sin City” where Americans, including San Diegans, could drink illegal hooch during Prohibition or where Hollywood stars could get a quickie divorce.

Yet increasingly, voices in both cities are looking to foster mutual respect and understanding — including in the border region between the metro areas.

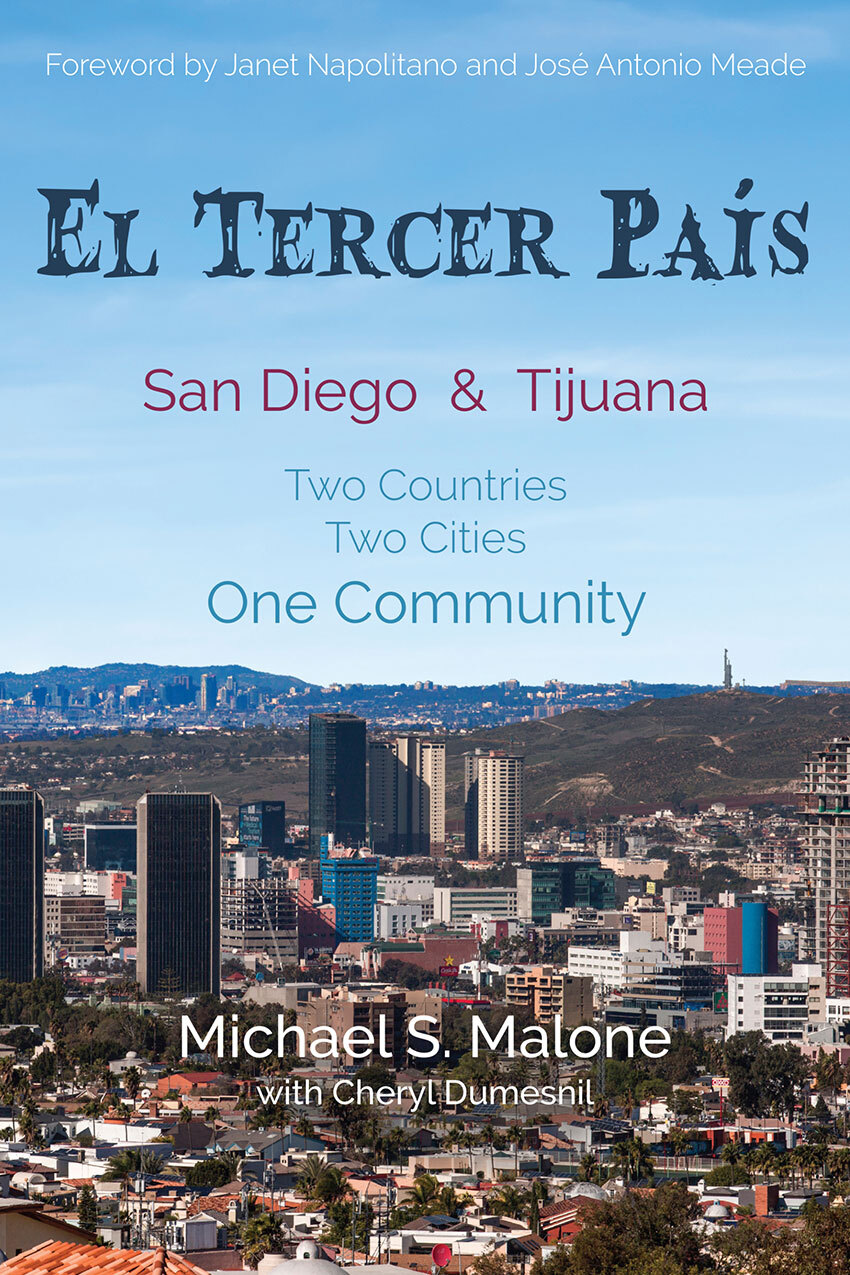

This is the premise of El Tercer País. San Diego and Tijuana: Two Countries, Two Cities, One Community, a new book by Silicon Valley-based journalist and author Michael Malone. Examining the Tijuana-San Diego relationship over time, Malone finds that it is shifting in surprising ways, resulting in a complex, nuanced portrait as the cities learn to work together across the border. The space between the cities, and the human interactions within this space, is what gives rise to the book’s title — The Third Country in English.

In the tercer país of the Tijuana-San Diego border, a half-million people cross legally each day, Malone said. Americans might come for a procedure at a skyscraper hospital that is part of Tijuana’s world-leading medical tourism industry. Mexicans might come to shop at the Mall of the Americas on the San Diego side.

These interactions result in stereotype-shattering statistics: more Mexicans shop on the American side than vice versa, and Tijuana — once a ranch village — now has more residents than its northern neighbor.

Malone notes that Tijuana and San Diego are “so close, they’re starting to bump into one another,” adding that this might literally be true at the Mall of the Americas: “I think one of the high-end retail stores … its wall almost touches the border wall … It’s how close the city of San Diego and its suburbs are pushing [to Tijuana]. They’re becoming a contiguous place.”

A tercer país is “the ultimate theme of the book,” Malone said, predicting “conversations between cities around the world on opposite sides of a border about the level of interaction … A common cause develops. They’ll be sharing best practices, teaching best practices, [becoming] interdependent … You’re going to see more of the model of a third country for two big metro areas.”

Malone’s previous nonfiction books include explorations of business, such as The HP Way and The Intel Trinity. In El Tercer País, business is among the factors helping to unite the borderlands. San Diegans, finding their home airport (San Diego International) too cramped, are increasingly turning to Tijuana International Airport as a more user-friendly option. Malone also praises outreach-oriented civic leaders such as Jose Galicot of Tijuana and Malin Burnham of San Diego.

A conversation with Galicot resulted in the book. Galicot asked Malone to write a book about the Tijuana-San Diego relationship as a feature of the 2020 Tijuana Innovadora event. Malone accepted but encountered challenges, including a time frame of six months and a relative lack of source material.

“There have been books about the history of Tijuana and books about the history of San Diego, but none [about] them in relation to each other,” he said.

He sought the perspective of individuals who helped shape this relationship, crediting his editor Cheryl Dumesnil with doing many of the interviews. Those who shared insights included former Mexican foreign minister Jose Antonio Meade and former U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano, who teamed up to write the foreword.

For the beginnings of the cities’ relationship, Malone had to turn much further back in time — first to Spanish beginnings in the New World, then to Mexican independence and the Mexican-American War, ended by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. The U.S. originally wished to take not only San Diego as part of the Mexican cession, but also Tijuana. Although Mexico kept Tijuana, the final treaty was nevertheless a bitter loss of territory.

In the 20th century, more promising interactions developed between Tijuana and San Diego. An early example paradoxically took place during another conflict — the Mexican Revolution, when government and revolutionary forces clashed in the Battle of Tijuana in May 1911. Civilians fled Tijuana for San Diego, where they joined Americans watching as Mexican insurrectionists — aided by some volunteers from the U.S. — defeated the federal forces.

The 1920s inaugurated what Malone called the dark years when San Diegans and other Americans traveled to Tijuana to indulge in pursuits that were forbidden up north.

“Prohibition kind of introduced the idea of Tijuana becoming Sin City,” Malone said. “San Diego was happy to export all of its societal ills to Tijuana.”

As bars opened for thirsty tourists, Tijuana also became notorious for brothels, bullrings and organized crime, Malone said. However, the city had its breaking point. During World War II, San Diego became an Allied maritime hub, and sailors and soldiers stationed there headed south for wild nights in Tijuana before shipping out to the Pacific. The Marines once reportedly got so rowdy that they were expelled for a time.

In peacetime, the inter-city relationship became more promising, with Americans venturing south not for bars and booze but for family vacations on the new highway system. Later in the 20th century, prominent San Diegans and Tijuanenses started major attempts at outreach — including a now-legendary dinner about three decades ago.

Malone cited this gathering, along with complementary, decades-long work by the University of California, San Diego, as an attempt to “begin to try to create a regional conversation.”

As the conversation increased, including in the San Diego Dialogue, so did the challenges. Malone details the international free trade talks between Mexico and the U.S. that resulted in NAFTA, the rise of the maquiladora system, the challenges of undocumented immigration and the rise of the drug cartels, as well as the environmental impacts of smog and water usage.

These challenges, he says, continue to be addressed by civic leaders who have helped raise awareness and cooperation among their respective national governments.

Yet the statistics remain grim in Tijuana: it leads the world in the per-capita murder rate and it has the highest number of femicides in Mexico.

“The cartels keep trying to take over Tijuana; the opportunities there kind of ebb and flow,” Malone said. “I’m pretty optimistic Tijuana will win.” He noted, “I know there’s an enormous amount of cooperation with the U.S. police, the San Diego police, the Chula Vista police, the Border Patrol.”

This year has witnessed the additional, unprecedented challenge of Covid-19. The pandemic initially resulted in Mexico shutting down its border with the U.S. to prevent infected Americans from entering; now, with the pandemic worsening in Mexico, it is the U.S. that has closed off its border, Malone said.

Turning to another major issue of this year, the U.S. presidential election and its aftermath, Malone predicts that the Biden administration will find it hard to stop momentum toward a border wall and that a push for open borders might encounter resistance from both Americans and Mexicans.

Amid the changes of 2020, Malone envisions that Tijuana and San Diego will continue their progress toward a precedent-setting model.

“I’m optimistic about the future,” he said. “The two cities represent the way the world is going to go.”