Latin America’s two largest countries have both gone to the polls in 2018, but the results could not have been more different.

In Mexico, leftist Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) rode a wave of anti-establishment sentiment in Mexico and turned it into an electoral tsunami, claiming nearly half of the popular vote and securing large congressional majorities for his party, Morena, created just five years earlier.

Meanwhile, in Brazil, the far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro fell just four per cent short of winning the presidency in the first round and will be hard to beat in the second round on 28 October.

The similarities between both candidates are as stark as their ideological differences. Both are populists with idealised visions of their respective countries’ pasts. In AMLO’s case, the era of nationalist, inward-oriented development during the 1960s and 70s. For Bolsonaro, the military dictatorship of 1964-85, which was also a period of rapid growth.

AMLO wants the state to play a greater role in the country’s economic development. Bolsonaro has appointed a University of Chicago-educated banker as his proposed finance minister.

AMLO wants inclusion for Mexico’s most marginalised and disenfranchised groups. Bolsonaro has spouted violent, discriminatory discourse against the country’s black, indigenous, gay, and female populations.

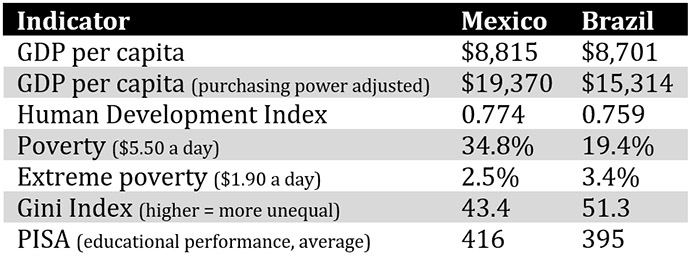

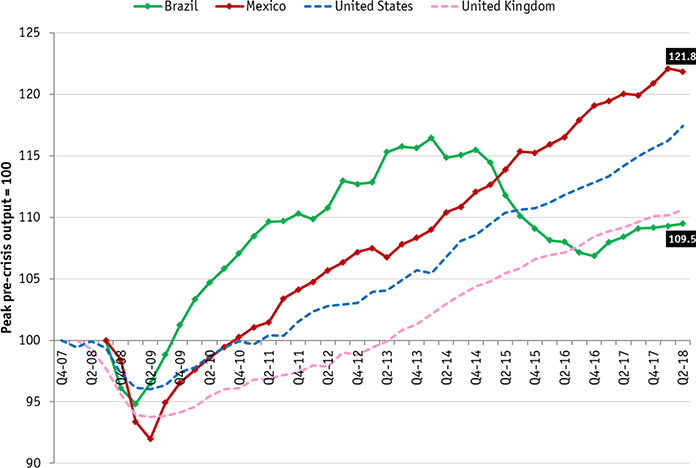

How could two Latin American countries with such similar levels of socioeconomic development (as illustrated below) spawn such dissimilar anti-establishment forces in the same year?

Source: IMF, UN, World Bank, OECD (latest available year)

1. Race

Westerners seldom realise that Latin America was the world’s first major melting pot, thanks to the confluence of Spanish and Portuguese colonists with the native inhabitants and large numbers of African slaves. Unlike in English, French, or Dutch colonies, intermixing was common, resulting in racial caste systems that have persisted from the colonial period to this day.

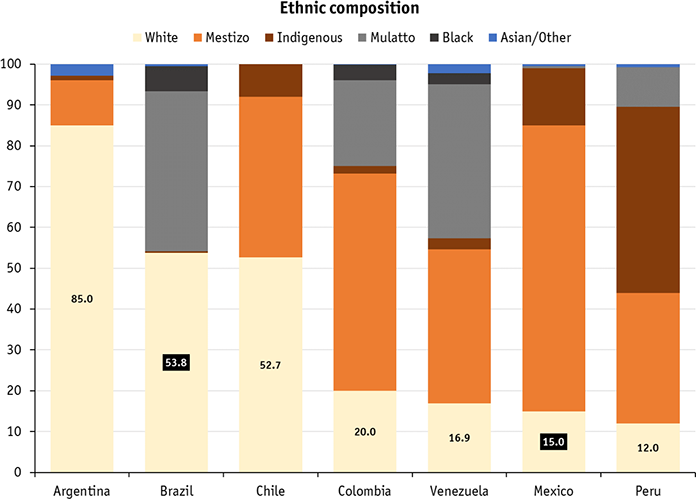

In almost all cases, whites made up the economic and political elites, followed by mixed-race groups in the middle, with black and indigenous people at the bottom. Although this pattern repeated itself throughout the region, Mexico and Brazil’s demographic profiles are vastly different.

Mexico, unlike, Brazil, was a major Pre-Columbian population centre, which has meant that most of the population is of indigenous or mixed-race descent. Mexico’s white population is small, at just 15 per cent, though they are disproportionately wealthy.

In contrast, Brazil’s white population is estimated at around half of the total, having been boosted by waves of European immigration in the late 19th and early 20th century, particularly in the country’s temperate south.

With such a sizeable white population, it should not come as any surprise that white supremacy is also rife: Brazil provides the fourth largest share of traffic to Stormfront, one of the oldest and largest white supremacy forums on the internet.

While racism in Mexico is all too present, particularly against indigenous citizens, the country’s 80 per cent non-white population means that making race a central pillar of your political platform would be electoral suicide.

Source: Lizcano Fernández, Francisco (2005), “Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI”

2. Religion

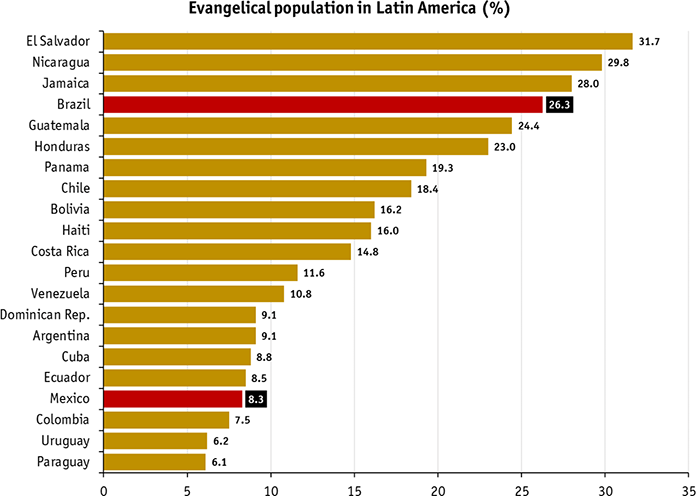

Evangelicalism has long been associated with extreme political conservatism in the US, and its spread to Latin American in recent decades has also come with increased electoral support for right-wing populists.

In some cases these candidates have been evangelicals themselves. Jimmy Morales was elected in Guatemala in 2015, for example, whereas Fabricio Alvarado came close earlier this year in Costa Rica. Both countries have large and rapidly growing evangelical populations. But by far the biggest evangelical population amongst Latin America’s larger countries is found in Brazil, where it is estimated at over a quarter of the total.

Taking their cue from their US brethren, Latin America’s evangelicals are far more politically active than their Catholic counterparts, and they consistently rally behind the most extreme, socially conservative candidates. For them, issues such as opposition to abortion and gay marriage take precedence over other political and economic issues. Although Bolsonaro is not evangelical, he has been wholeheartedly endorsed by Brazil’s evangelical leaders, who find much to like in his support for traditional social norms and his anti-progressive rhetoric.

In contrast, Mexico has one of the region’s smallest evangelical communities, at less than 10 per cent of the population (see below). Although an evangelical party, the Social Encounter Party (PES), figured incongruously in AMLO’s winning coalition, they received such a small share of votes that they were struck off the national party registry in September (though they will keep their relative majority seats in Congress).

Source: Operation World

3. Outsider appeal

AMLO may have run as an anti-establishment candidate, but he has spent the entirety of his political career within a major party: first, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) during the era of one-party rule, then the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD), and finally Morena, which he created after his 2012 electoral defeat, absorbing many PRD malcontents in the process. The Mexican political system is not friendly to outsiders. So much so that until 2013 independent candidates were even barred by law from running.

In contrast, Brazil’s highly fragmented democracy is very appealing to upstarts. Both countries have similarly sized lower houses, with 500 seats in Mexico and 513 in Brazil. But whereas Mexico’s majority coalition controls 313 seats with just three parties (255 from Morena alone), Brazil’s majority coalition holds 315 seats with no less than 11 parties, only 51 of which are held by the ruling Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB).

In total there are 25 parties with representation in Brazil’s chamber, compared to nine in Mexico. As for Bolsonaro, his Partido Social Liberal (PSL) has just eight seats in the current legislature, though that figure will jump to 52 once the newly elected legislature is inaugurated in January. By Mexican standards, that would still be a pittance.

Mexico’s main right-wing party, the National Action Party (PAN), remains the largest amongst the opposition. But despite having some very socially conservative factions, it is mostly a party of technocrats rather than populists. A far-right populist in Mexico would have to swim against the tide of a political system that stacks the odds against minority parties and independents.

4. Crime and punishment

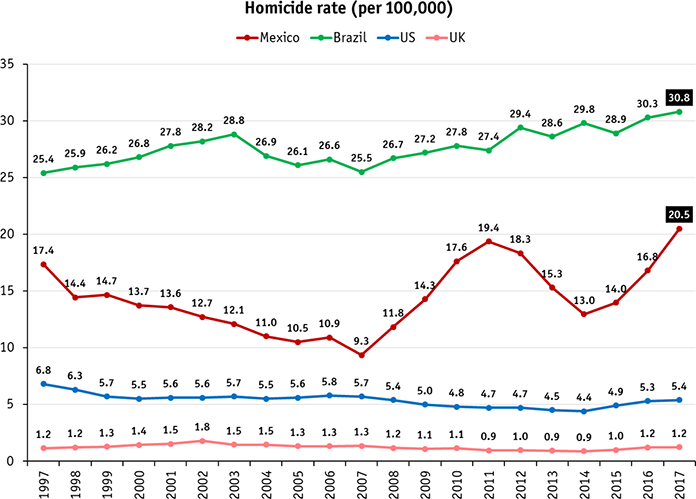

Mexico’s gruesome drug war may make the headlines, but it’s easy to forget that Brazil is the more violent country overall, with a homicide rate 50 per cent higher (see below) and a larger number of cities listed amongst the world’s most violent.

Source: Atlas da Violência (Brazil); Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública (Mexico); FBI (US); ONS (UK)

Making matters worse, Brazil’s crime rates have been rising in recent years. Even though this rise has been much less drastic than Mexico’s recent surge in drug-related killings, it has led many Brazilians to sympathise with Bolsonaro’s “tough on crime” posture, his disdain for human rights, and his proposals to reintroduce capital punishment and liberalise gun laws.

Similar proposals might have mass appeal in Mexico were it not for the fact that Mexicans already know what a full-frontal assault on organised crime begets: even more violence. This was evidenced by the surge in homicides after then-president Felipe Calderon sent the Army and Marines against the cartels shortly after he took office in December 2006.

Human rights violations by the military have also weighed heavily on the public mind. While most Mexicans have reacted with cynicism to AMLO’s conciliatory security proposals, including a controversial “amnesty” for low-level criminals, that does not necessarily mean that they would embrace a Bolsonaro-style security agenda.

Concerns about crime also coalesce with the issue of race. Racial-socioeconomic divides in Brazil make it relatively easy to create racist associations between criminality and skin colour, even though controlling for income levels makes any such association statistically irrelevant. In this sense, Brazil’s racially charged attitudes to crime resemble those in the US far more than in Mexico. This provides a premium for politicians like Bolsonaro who are willing to make a discursive link between crime and skin colour.

5. The economy

Brazil is only gradually recovering for an economic crisis that began in 2014 and ultimately wiped out around eight per cent of GDP, from peak to trough. This coincided with the Lava Jato corruption scandal, which tarnished the legacy of the left-wing Workers’ Party (PT) in power at the time.

Although Bolsonaro’s hardcore supporters may be more excited about his social stances and security agenda, his pro-market sympathies are also seen by many as an alternative to a bloated state and an inward-looking economy that has lost much of its lustre since the glory days when the BRICs seemed ready to inherit the earth.

This is not to say that Bolsonaro is a bona fide free-market capitalist. Far from it. His nationalist economic views have traditionally been much more in line with AMLO’s, and he does not appear at all comfortable discussing economic policy on the campaign trail. But he has appointed a “Chicago Boy”, Paulo Guedes, as his pick for finance minister, and his views have become more business-friendly.

Markets have responded enthusiastically, with stocks rallying after his first-round win. And given a choice between him and the PT, Brazil’s centre-right voters will happily overlook Bolsonaro’s extreme views on other issues. Tellingly, the ruling MDB has recently stated that it will remain “neutral” for the second round vote, which is an endorsement for Bolsonaro in all but name.

Sources: BCB (Brazil), INEGI (Mexico), BEA (US), ONS (UK)

Although Mexico has not suffered a crisis as severe as Brazil’s since the 1990s, its relatively insipid growth rate in the post-NAFTA era has fuelled increasing scepticism about the country’s market-oriented economic model. AMLO’s appeal as the only candidate willing to challenge Mexico’s business class and sever the links between political and economic power was one of his strongest selling points for a public no longer convinced that free markets can provide them with the opportunities that they deserve.

Could Mexico veer to the far right?

Though the ideological divergence of Mexican and Brazilian voters is underpinned in part by relatively stable structural factors like racial and religious demographics, it would be extremely naive to think that Mexico will remain immune to the allure of far-right populism over the coming decade.

The country still has strong anti-progressive undercurrents, not least on the internet. The rule of law is still fragile, and growing crime and corruption could further undermine social cohesion. The economy could still remain sluggish or – in the worst case scenario – fall back into recession. All of these factors leave the left vulnerable to a right-wing populist counterattack in 2024.

How this far right populism might manifest itself is less clear. Just like the Republican Party in the US, the PAN could shed its technocratic veneer if it sees populism as a more effective way of returning to power. A new outsider could also emerge, particularly if Morena seeks to entrench itself in power, thereby stoking opposition to the party system.

However it unfolds, believing that it couldn’t happen in Mexico is precisely the kind of wishful thinking that makes it more likely that it will.