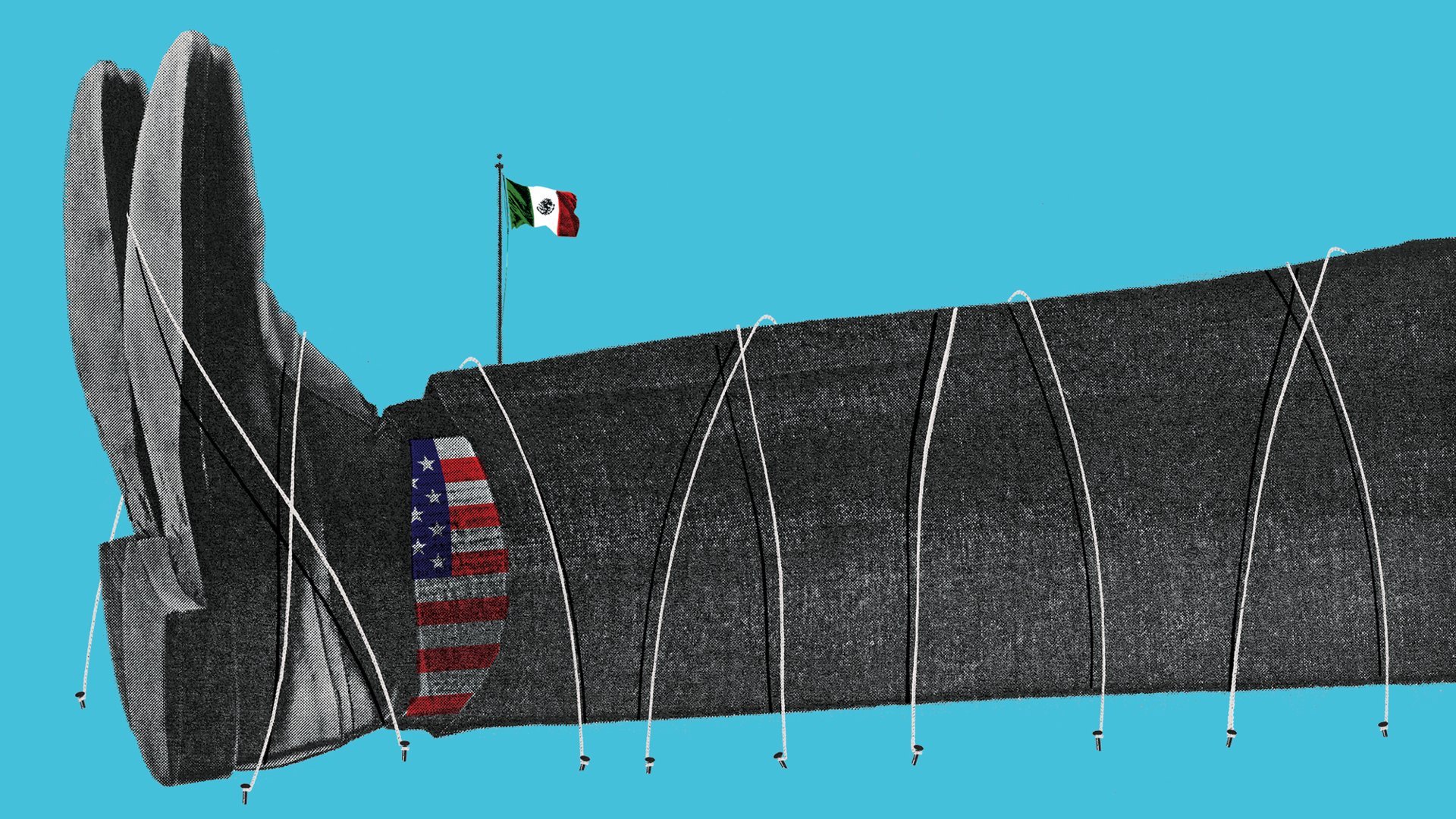

When Donald Trump first made sport of thumping Mexico—when he accused America’s neighbor of exporting rapists and “bad hombres,” when he deemed the country such a threat that it should be contained by a wall and so clueless that it could be suckered into paying for its own encasement—its president responded with strange equilibrium. Enrique Peña Nieto treated the humiliation like a meteorological disturbance. Relations with the United States would soon return to normal, if only he grinned his way through the painful episode.

In August, Peña Nieto invited Trump to Mexico City, based on the then-contrarian notion that Trump might actually become president. Instead of branding Trump a toxic threat to Mexico’s well-being, he lavished the Republican nominee with legitimacy. Peña Nieto paid a severe, perhaps mortal, reputational cost for his magnanimity. Before the meeting, former President Vicente Fox had warned Peña Nieto that if he went soft on Trump, history would remember him as a “traitor.” In the months following the meeting, his approval rating plummeted, falling as low as 12 percent in one poll—which put his popularity on par with Trump’s own popularity among Mexicans. The political lesson was clear enough: No Mexican leader could abide Trump’s imprecations and hope to thrive. Since then, the Mexican political elite has begun to ponder retaliatory measures that would reassert the country’s dignity, and perhaps even cause the Trump administration to reverse its hostile course. With a presidential election in just over a year—and Peña Nieto prevented by term limits from running again—vehement responses to Trump are considered an electoral necessity. Memos outlining policies that could wound the United States have begun flying around Mexico City. These show that Trump has committed the bully’s error of underestimating the target of his gibes. As it turns out, Mexico could hurt the United States very badly.

The Mexico–U.S. border is long, but the history of close cooperation across it is short. As recently as the 1980s, the countries barely contained their feelings of mutual contempt. Mexico didn’t care for the United States’ anticommunist policy in Central America, especially its support of Nicaraguan rebels. In 1983, President Miguel de la Madrid obliquely warned the Reagan administration against “shows of force which threaten to touch off a conflagration.” Relations further unraveled following the murder of the DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena in 1985. Former Mexican police officers aided drug traffickers who kidnapped and mercilessly tortured Camarena, drilling a hole in his skull and leaving his corpse in the Michoacán countryside. The Reagan administration reacted with fury at what it perceived as Mexican indifference to Camarena’s disappearance, all but shutting down the border for about a week. The episode seemed a return to the fraught days of the 1920s, when Calvin Coolidge’s administration derided “Soviet Mexico” and Hearst newspapers ginned up pretexts for a U.S. invasion.

Once the threat of Soviet expansion into the Western Hemisphere vanished, the United States paid less-careful attention to Latin America. It passively ceded vast markets to the Chinese, who were hunting for natural resources to feed their sprouting factories and build their metropolises. The Chinese invested heavily in places like Peru, Brazil, and Venezuela, discreetly flexing soft power as they funded new roads, refineries, and railways. From 2000 to 2013, China’s bilateral trade with Latin America increased by 2,300 percent, according to one calculation. A raft of recently inked deals forms the architecture for China to double its annual trade with the region, to $500 billion, by the middle of the next decade. Mexico, however, has remained a grand exception to this grand strategy. China has had many reasons for its restrained approach in Mexico, including the fact that Mexico lacks most of the export commodities that have attracted China to other Latin American countries. But Mexico also happens to be the one spot in Latin America where the United States would respond with alarm to a heavy Chinese presence.

That sort of alarm is just the thing some Mexicans would now like to provoke. What Mexican analysts have called the “China card”—a threat to align with America’s greatest competitor—is an extreme retaliatory option. Former Mexican Foreign Minister Jorge Castañeda told me he considers it an implausible expression of “machismo.” Unfortunately, Trump has elevated machismo to foreign-policy doctrine, making it far more likely that other countries will embrace the same ethos in response. And while a tighter Chinese–Mexican relationship would fly in the face of recent economic history, Trump may have already set it in motion.

The painful early days of the Trump administration have reminded Mexico of a core economic weakness: The country depends far too heavily on the American market. “Mexico is realizing that it has been overexposed to the U.S., and it’s now trying to hedge its bets,” says Kevin Gallagher, an economist at Boston University who specializes in Latin America. “Any country where 80 percent of exports go to the U.S., it’s a danger.” Even with a friendly American president, Mexico would be looking to loosen its economic tether to its neighbor. The presence of Trump, with his brusque talk of tariffs and promises of economic nationalism, makes that an urgent task.

Until recently, a Mexican–Chinese rapprochement would have been unthinkable. Mexico has long steered clear of China, greeting even limited Chinese interest in the country with wariness. It rightly considered China its primary competition for American consumers. Immediately after nafta went into effect in 1994, the Mexican economy enjoyed a boom in trade and investment. (A flourishing U.S. economy and an inevitable turn in Mexico’s business cycle helped account for these years of growth too.) Then, in 2001, the World Trade Organization admitted China, propelling the country further into the global economy. Many Mexican factories could no longer compete; jobs disappeared practically overnight.

Mexico’s hesitance to do business with the Chinese was also a tribute to the country’s relationship with the “Yanquis.” A former Mexican government official told me that Barack Obama’s administration urged his country to steer clear of Chinese investment in energy and infrastructure projects. These conversations were a prologue to the government’s decision to scuttle a $3.7 billion contract with a Chinese-led consortium to build a bullet train linking Mexico City with Querétaro, a booming industrial center. The cancellation was a fairly selfless gesture, considering the sorry state of Mexican infrastructure, and it certainly displeased the Chinese.

But China has played the long game, and its patience has proved farsighted. The reason so many Chinese are ascending to the middle class is that wages have tripled over the past decade. The average hourly wage in Chinese manufacturing is now $3.60. Over that same period of time, hourly manufacturing wages in Mexico have fallen to $2.10. Even taking into account the extraordinary productivity of Chinese factories—not to mention the expense that comes with Mexico’s far greater fidelity to the rules of international trade—Mexico increasingly looks like a sensible place for Chinese firms to set up shop, particularly given its proximity to China’s biggest export market.

Mexico began quietly welcoming a greater Chinese presence even before the American presidential election. In October, China’s state-run media promised that the two countries “would elevate military ties to [a] new high” and described the possibility of joint operations, training, and logistical support. A month and a half later, Mexico sold a Chinese oil company access to two massive patches of deepwater oil fields in the Gulf of Mexico. And in February, the billionaire Carlos Slim, a near-perfect barometer of the Mexican business elite’s mood, partnered with Anhui Jianghuai Automobile to produce SUVs in Hidalgo, a deal that will ultimately result in the production of 40,000 vehicles a year. These were not desultory developments. As Beijing’s ambassador to Mexico City put it in December, with the American election clearly on the brain: “We are sure that cooperation is going to be much strengthened.”

Let’s pause to consider the illogic. Trump says that China is a grave threat, both militarily and economically. He has accused China of “rap[ing] our country.” That’s not the way most analysts would put it, but a fairly broad bipartisan consensus holds that China’s expansionism should be contained and its mercantilism checked. Barack Obama’s vaunted “pivot” to Asia tried to keep China’s neighbors from succumbing to its gravitational pull. Thanks to Donald Trump, China is now better positioned to execute the most difficult maneuver in its own, North American pivot—pushing the U.S. and Mexico further apart.

Even before donald trump’s foray into presidential politics, Mexico was a primary subject for incendiary right-wing news accounts. During the Obama years, conservative media in the U.S. blared unsubstantiated stories about Islamic State operatives camping out in Ciudad Juárez, waiting to commit car bombings across the border. It was reported on Fox News that copies of the Koran had been strewn along smuggling routes into Texas. Of course, the idea of terrorists slinking into the country isn’t itself outlandish. But these stories shared a profoundly faulty core assumption: that somehow the Mexican and U.S. governments were blasé about the threat.

One common complaint of populists, no matter their country, is that their nation has ceded sovereignty. This, in fact, has happened in Mexico’s case. The shock of September 11, and the immediate imperative of preventing a sequel, joined Mexico and the U.S. together. Their security services began sharing information, an exchange that became casual, almost automatic. When I called up an American official who served in the Department of Homeland Security, he recounted the ways in which the Mexican government has been integrated into U.S. counterterrorism efforts. The passenger list of every international flight that arrives in Mexico is run through American databases, and the results are passed along to American officers, some of whom are posted in Mexico City’s Benito Juárez airport. Cargo bound for the United States is inspected before it leaves Tijuana. In Virginia, Mexican officials sit in the National Targeting Center, which monitors the comings and goings of international cargo. The American official told me, “They would never balk by saying, ‘This isn’t in our interest.’ What’s in the interest of one is considered to be in the interest of the other.” Given the length of the shared border, and the fact that it is the most frequently crossed border in the world, the perfect success rate of these measures to date is a bureaucratic and diplomatic feat.

Mexico could assert its importance by dialing back these efforts. What seems more likely is that relations between the security agencies will slowly decay, as trust between the two countries evaporates and warm feelings give way to tensions. America’s everyday relationship with Mexico is like The New York Times’ presence at White House press briefings or a president’s avoidance of conflicts of interest: It’s a modern norm that seems a fixture of governance, until it erodes and perhaps irreversibly disappears.

So much of Donald Trump’s rise was predicated on a nonexistent fear: that Mexicans are pouring over the border. In fact, more Mexicans now leave the United States each year than arrive. But Trump could inadvertently trigger the waves of newcomers that he rails against. For the past few years, the border has been periodically flooded with Central Americans fleeing gang violence. Those surges could have been far larger had Mexico not stepped up enforcement of its southern border with Guatemala in 2014, largely stanching the flow of migrants. From 2014 through July 2016, with American prodding, the Mexicans detained approximately 425,000 migrants who were attempting to make their way to the United States.

Recently, however, migrants and their smugglers have found new routes through the reinforced border, and the number of Central Americans reaching the United States is again climbing. If Mexico were to conclude that there is little upside to its expensive efforts, the U.S. could find itself facing a genuine immigration crisis. The moral case for the United States’ welcoming these migrants is strong, but a sudden influx could overwhelm the American immigration system, straining budgets and exceeding the capacities of courts and detention centers.

Trump’s rush toward hard-line immigration policies could yield a grim bonanza of other unintended consequences. Mass deportations of Mexicans could uproot hundreds of thousands and deposit them on the other side of the border, forcing their reintegration into lives they left, many of them long ago. Perhaps the Mexican economy, the 15th-largest in the world, has the capacity to absorb these refugees from Trump’s America. But it’s equally easy to imagine a scenario in which they inundate the labor market. And even that possibility doesn’t begin to capture the likely economic costs of deportation. The Mexican economy would be deprived of the remittances that immigrants send back to their relatives. It’s hard to speak hyperbolically about the importance of these transfers—in 2016, Mexican Americans sent $27 billion back to their Mexican families, more than the value of the crude petroleum Mexico exports annually. Remittances are extensively studied by economists. Ample evidence suggests that they are as effective an antipoverty program as anything devised by governments or NGOs: Families that receive remittances are more likely to invest in their own health care and education. Relieved of the daily scramble for sustenance, they are free to participate in productive economic activity with lasting benefits.

If the Trump administration were to engage in mass deportations that choked the flow of remittances at the same time it engaged in a trade war with Mexico, it would wreck the Mexican economy, generating the sort of conditions that have, in the past, triggered waves of migration northward. Even if the likelihood of getting caught were far greater than before, the threat of capture wouldn’t necessarily deter migrants. History vividly shows that desperate people take risks that might otherwise appear irrational.

These scenarios may seem unimaginably distant, especially under current political circumstances. Peña Nieto has cautiously ambled into the Trump era, in keeping with his bland suavity. Mexico has much to lose from brinkmanship and blustery threats—perhaps more than the United States does. But Mexican prudence might not persist. Next year, the country will pick a new president. According to early polls, the likely winner is a familiar loser: the left-wing populist Andrés Manuel López Obrador—a k a Amlo, or, as the great Mexican intellectual Enrique Krauze dubbed him, the “Tropical Messiah.” Amlo lost his first presidential election, in 2006, by the thinnest of margins, and alleged that funny business cost him the presidency. His second defeat, six years later, was by a far wider margin. In both instances, his supporters took to the Zócalo, Mexico City’s main plaza, to noisily protest the results. In 2006, he even declared himself Mexico’s “legitimate president,” donning a red, white, and green sash of the sort that is ritualistically draped over the chief executive.

Amlo has squandered big early leads before, and is by no means an inevitability. Still, there’s a good chance that, in a year’s time, the populist Trump will be staring across the border at another populist. The differences between Trump and López Obrador are immense, and a potential source of combustion, but similarities also abound. Amlo’s political party is called the National Regeneration Movement (morena)—he wants to make Mexico great again. Like Trump, Amlo professes an almost mystical connection with the people. He alone can channel their will.

Pundits are fond of placing López Obrador in the same genre as Venezuela’s late strongman Hugo Chávez. That comparison might overstate his danger. During this campaign, Amlo has embraced a more business-friendly persona—the sort of savvy repackaging that helped longtime runner-up Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva climb to power in Brazil. Still, López Obrador has been very clear about his attitude toward the United States. He despises collaboration with the DEA and relishes the idea of renegotiating nafta on terms more favorable to Mexico. “Everything depends on strengthening Mexico,” he has said, “so we can confront aggression from abroad with strength.” If Amlo becomes president, all of the worst-case scenarios, all of the proposals for petulant retaliation, would become instantly plausible.

Not so long ago—for most of the postwar era, in fact—the United States and Mexico were an old couple who lived barely intersecting lives, hardly talking, despite inhabiting the same abode. Then the strangest thing happened: The couple started chatting. They found they actually liked each other; they became codependent. Now, with Trump’s angry talk and the Mexican resentment it stirs, the best hope for the persistence of this improved relationship is inertia—the interlocking supply chain that crosses the border and won’t easily pull apart, the agricultural exports that flow in both directions, all the bureaucratic cooperation. Unwinding this relationship would be ugly and painful, a strategic blunder of the highest order, a gift to America’s enemies, a gaping vulnerability for the homeland that Donald Trump professes to protect, a very messy divorce.