The Mexicans were not the first people to fall under the shadow of Donald Trump’s political slanders (an honor belonging to Barack Obama, object of the birther mania), and they may be not his target at this very moment. But the slanders against them may, even so, have outdone everything else in generating the American political atmosphere right now. It was vilification of Mexicans that led to Trump’s decisive triumph over his many rivals in the Republican primaries of 2016. He shocked everyone with his insults about rapists and criminals, and shocked everyone anew with his refusal to apologize for the original shock, and shocked everyone yet again with his disparagement of Judge Gonzalo Curiel in the Trump University fraud case. And the repeated shocks aroused a popular excitement. Masses of Americans not only cheered, they chanted, such that “Build the wall!” became a main slogan of Trump’s campaign, more insistently even than “Lock her up!”

He will, of course, build it, and there is reason to believe that, once he has done so, his public will cheer and chant still more lustily, thrilled to discover that here, at last, is a leader who fulfills his promises, and thrilled at the wall itself, and thrilled at the chilly message his wall will send to Muslims and any number of other people, not excluding the half of America that did not vote for Donald Trump. The wall in these respects will turn out to be a national monument, dedicated to the promotion of civic values, in its fashion. It will be the anti-Statue of Liberty. It will engrave vilification of Mexicans into the national landscape. And all of this, the blossoming of the new national mood, requires a response, which ought to be, above all, a defense of Mexicans, not just on narrow political or economic grounds, but culturally, as well—a defense that bears on American civilization.

About the Mexican immigrants, then, the people who are so massively despised—about these people it should be remembered that, from a long-range historical perspective, they ought not to be pictured as immigrants at all, not in the full and classic sense of the word. A classic immigrant was Donald Trump’s grandfather, who came from Germany in the 1890s and vigorously pursued the American Dream in its rags-to-disrepute version—a man who made a fortune running brothels in the American Northwest and the Yukon, and converted the fortune to real estate, which his son converted into a larger fortune by discriminating against blacks, which Donald Trump himself has converted into a still larger fortune through business practices whose inner workings he has preferred to conceal. But this is not the Mexican story.

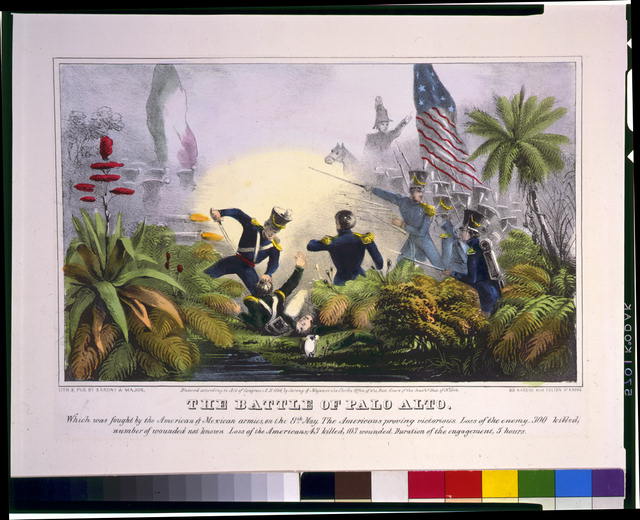

In America’s southwestern quadrant, it was not the fortune-seeking Mexicans who descended upon the United States, but the fortune-seeking Americans who descended upon Mexico, as a consequence of America’s triumphs in the Mexican-American War of 1846-48. During the terrible years of the Mexican civil war early in the 20th century, the waves of Mexicans who fled northward to the United States were, in a sense, merely rejoining their long-lost cousins—people who fled from the part of mutilated Mexico that had fallen into civil war to the part that had fallen into American hands. The Spanish language those people spoke was the old language in the American Southwest, just as it was in Florida and a few other places. Spanish is the second language in the United States today because it has always been the second language, except in regions where it used to be the first language. And the Mexican presence in the United States touches on something deeper yet.

The early English colonists in North America were brutal people who presided over the collapse and flight of the Indian tribes and sometimes over their extermination. And the English settlers refused, on racial grounds, to intermarry, which meant that, when the United States began to take shape as a political society and as a culture, the number of Americans who felt any connection to the Indians and to the Indian past was relatively small. The writers who founded American literature in the early and mid-19th century used to worry about this, in the belief that a proper civilization requires a sense of antiquity. And the writers did everything they could do to make up for the lack. To draw a portrait of America with an ancient Indian background was the literary program of James Fenimore Cooper, Francis Parkman, Whittier, Longfellow, and sometimes Thoreau. Only, the program lost currency after a while. The writers in subsequent generations took less interest in it, perhaps because they found that, with the eclipse of the tribes, it was becoming more difficult to engage the topic. The filmmakers in the 20th century revived the old literary program, for a while—yet the filmmakers, too, wearied of Indian themes, after a few decades.

Mexico’s history has trod a different path, however, and this was so from the start. It may be that, in Mexico, the Indian civilizations were too large and sophisticated to be fully massacred or driven away by the early Spanish conquistadors and settlers. Or maybe the Spanish imagination proved to be more flexible and generous, on certain topics, than the English imagination. In Mexico, in any case, the colonists did intermarry, which meant that, in time, a new race emerged. The 19th-century Americans customarily disdained the Mexicans as half-breeds (and, to be sure, the contempt doubtless persists today among the chanting crowds). But the Mexicans looked on the racial questions from an opposite perspective. The cultural theoretician of the Mexican Revolution was José Vasconcelos, who regarded Mexico’s population as the “cosmic race,” which, far from being inferior, commanded powerful cultural traits—a cosmic race that drew on all parts of the world, and could look back upon the Spanish past and the history of Christianity and the mystical truths of Plotinus; and could look back upon the Indian past of the Aztecs and the Mayas and the other Indian nations. The cosmic race was, in short, a people with a profound and unusually complex and cosmopolitan sense of civilization, which, in its august antiquity, was superior to the anti-historical, racially narrow culture of the Anglos to the north.

The brilliance of Mexico’s literature has owed something to these ideas from the start. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the founder of Mexican literature—altogether a genius—went so far as to write poetry in the Aztec language. And her embrace of the Indian heritage was Ramón López Velarde’s a couple of hundred years later, and Octavio Paz’s, and thus onward to, for instance, our contemporary Carmen Boullosa, in whose novel from a year or two ago, Texas: The Great Theft, you will find angry Mexicans of the 1850s launching armed insurrections against the rapacious Texas gringos amidst crowds of borderless Apaches and other peoples—a book for the Trumpian age. It is true that Mexicans themselves sometimes feel a little embarrassed by their own fascination with the distant past. They worry about an Indian shtick in their literature, and they worry about D.H. Lawrence and the non-Mexican tourist romantics of Mexican barbarism. Those are reasonable worries—and, even so, the Mexicans, with their more than three centuries of literary meditation on the Hispano-Indian double identity, do command a tremendous cultural wealth, and they know they do.

They carry the wealth everywhere they go. Paz remarks somewhere that, in bringing their national food to the United States, the humblest of Mexican immigrants restore America to its roots, which is undeniable. Mexican cuisine is, after all, largely a pre-Columbian creation, which means that every tiny taqueria pays homage to the American past, as cannot be said of the American hamburger homages to Germany. I am not qualified to speak about Mexican Catholicism (except to observe that, in its Mexican version, Catholicism contains syncretically the Indian past; and the religious architecture of Mexico is sometimes magnificent precisely because of a baroque mingling of the Spanish and the Aztec, which is something that cannot be seen in the religious architecture in the United States; and Sor Juana’s baroque Catholicism and Vasconcelos’s cosmic-race Catholicism are enchantingly Platonist). But I do observe that, in matters of high culture, Mexico’s civilization, with its Catholic roots, assumes a different hue than America’s civilization, with its Protestant roots. A main American attitude about Mexico tends to suppose, perhaps without saying so, that America’s culture must generally be superior, given how dynamic the United States has proved to be.

But it should be remembered that, among the Latin Americans, the normal assumption has sometimes pointed the other way, in the belief that, if there is a national culture lacking in depth and qualities of soul, surely it must be America’s. José Enrique Rodó, the Uruguayan writer, laid out the argument in its classic version in his essay, Ariel, from 1900, which all well-educated Mexicans used to read and maybe still read, but which, in proof of Rodó’s thesis, has scarcely been heard of by even the best-educated of Americans. The argument adds up to a Catholic (and Tocquevillean) brief against Protestantism and utilitarianism. It is an argument for granting to philosophy and the mystic love of beauty a loftier place than America’s business outlook will concede. It faults America accordingly. It shudders in distaste. Here is an anti-gringo-ism that gringos are too gringo-ish to understand. The argument leads it readers to see in the culture of Mexico a double advantage: the Mexican advantage in being more American than what passes for American culture (because Mexico’s culture is more firmly grounded in the Indian past); and the Mexican advantage in being more European and especially more French than American culture (because Mexico’s high culture, with its reliance on Latin tradition, conforms more closely to the French habits and instincts).

So the wall will go up, or maybe has already gone up, spiritually speaking; and it will cut us off, at least symbolically, from the Mexican advantages. It will shore up our American insularity. It will deepen our American amnesia. It will make us colder, instead of warmer. It will make our cheeks whiter, our foods blander, our r’s flatter, our colors paler, our literature less philosophical, our philosophy less literary, our command of languages poorer, our human sympathies more constricted. Or so I worry.

Do these worries seem over the top? In their defense, I point out that nothing I have said is even faintly original. You can see bits and pieces of my appreciation of the Mexican contribution to American culture in the founding literature of America—in Longfellow’s poetry, and in the histories of William Henry Prescott, and in the essays of Whitman. “The Spanish Element in Our Nationality” is the name of one of those essays, from November Boughs. By the “Spanish Element” Whitman means the Mexican element and the Spanish language both. He was a celebrator, and in that essay he celebrates. “O Libertad,” he exclaims in one of his poems. And, in saying this, never was he more acutely attuned to our own moment—this terrible moment when freedom—in Spanish!—is precisely the element in the American nationality that we most desperately need to revive—O Libertad: the necessary counterprogram to that most miserable of soulless business calculations, “America First.”