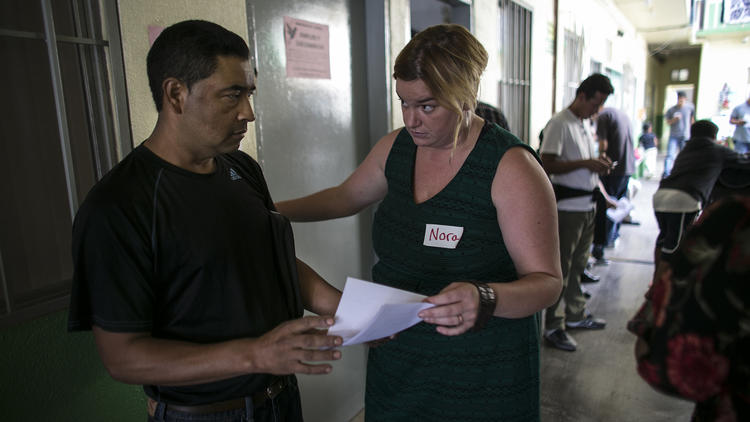

Nora Phillips stood five miles from the United States border in a hilltop neighborhood of cinderblock homes and low swooping electrical lines.

Inside the migrant shelter, hundreds of Mexicans, Central Americans and Haitians crowded, desperate for a way to cross into the U.S. — legally.

“Merci pour votre patience,” Phillips, 35, said, thanking the French-speaking Haitians for their patience.

Phillips, of East Los Angeles, was one of 45 immigration attorneys who had converged to hear their pleas.

Some had been deported before. Others were hoping to ask for asylum at the San Ysidro Port of Entry. Some had tales that many would find sympathetic; a few had back stories that would make others cringe.

Phillips had persuaded the other attorneys — some from as far away as New York — into volunteering in early October for a two-day legal clinic in Tijuana.

“At a minimum, in a democracy, you deserve to know what your rights are,” said Phillips, who guzzled down orange DayQuil as she fought a cold. Her 5-year-old daughter tagged along for the clinic. “My job as an attorney is to take a case at face value and assess whether you qualify for anything under the law that currently exists.”

The work Phillips and the other attorneys undertook was far from new. But it happens at a time when, more than any time in recent memory, the issue of mass migration — whether by immigrants from Mexico and Central America or refugees from Syria and other parts of the world — is generating intense global anxiety and setting the tenor for a presidential election.

“I don’t want to rip families apart,” Hillary Clinton said during the last presidential debate, reiterating a promise to pass comprehensive immigration reform to give legal status to millions in the country.

Donald Trump, who has espoused building a giant wall at the border with Mexico, claims Clinton wants “open” borders and accuses those in the country illegally of cutting in line.

“People are in line waiting to become a citizen,” he said, and others should wait their turn and apply to get into the U.S. legally. “It’s unfair someone can run in across the border and become a citizen.”

The people gathered at the shelter in Tijuana said they wanted to come to the U.S. legally. But unlike petitioners who ate educated professionals who work for companies in places like Silicon Valley, these were freighted with the baggage that comes from being poor and dispossessed.

In the shelter’s courtyard, one of the volunteer attorneys, Troy Elder, spoke in Creole to half a dozen Haitian men sitting in a circle around him.

After the devastating earthquake in 2010, thousands of Haitians journeyed to a then-booming Brazil, seeking refuge. But after that country’s economy was hit by recession, many of the Haitians migrated to the Mexico-U.S. border, drawn by a U.S. policy of not deporting Haitians at that time.

In September, the Obama administration reversed that policy and announced that deportations of Haitians would resume because conditions in their homeland had improved.

But Elder told the men that there was a chance that the destruction caused by Hurricane Matthew would prompt the U.S. to put the brakes — at least for a while — on deportations.

“Maybe the policy will reverse in the next few days. Just wait,” he told them, correctly predicting a delay in the deportation policy.

Those arguing for stricter immigration limits claim the efforts of people like Phillips enable unwanted immigration, while overwhelming courtrooms with dubious asylum claims.

“The sheer volume of such claims is being used to tie up the courts, which works to the advantage of those trying to game the system,” said Ira Mehlman, spokesman for the immigration restriction group Federation for American Immigration Reform.

Though unusual among those at the shelter, the case of Jose de Jesus Duarte Gonzalez — a Mexican man who has been deported on multiple occasions, including about a month ago — would be especially polarizing at a most polarizing time.

Duarte said he was desperate to get back to the U.S. to reunite with his 8-year-old son, Christian, who has Down syndrome. Duarte’s wife had just died of a heart attack at their Phoenix home, he said, so the boy was left without parents.

But Duarte had served prison time for domestic violence before his most recent expulsion. He blamed himself for that, as well as for a DUI charge.

“I regret everything I did,” he said. “But my son shouldn’t suffer because of it.”

Juan Carlos Pallares, an immigration attorney from Long Beach, referred Duarte to two attorneys in Arizona — but he did not send him off with much hope. Because of his dubious history, Duarte’s chances of being allowed to legally return to the U.S. were slim.

Without referring to Duarte, Phillips said there were some people she could not advocate for. And even if she did, she said, they would have virtually no chance of qualifying to reenter the U.S.

“I think that there are some individuals who have done really awful things and should not be in the U.S. … I believe they are a danger,” she said. “If you are my client, I will advocate like hell for you but there are some cases where I’m not going to be able to advocate.”

Then there are other people who simply don’t have strong enough cases.

“A lot of times the advice is you really don’t qualify for anything. You don’t have any relief,” Phillips said, adding that a condition of the legal clinics is that the person be low income.

The attorneys help those deemed good candidates for relief to obtain pro bono representation and prepare them to give themselves up at the San Diego Port of Entry.

Through a Spanish-language interpreter, volunteer and Laguna Niguel resident Iris Anderson told Jhanny Rolando Seoanes Chavez that if she were to pass a “credible fear” interview with immigration officials, she would probably have to remain in a detention facility for months.

Seoanes is a transgender woman who fled Honduras after her father kicked her in the face and dislocated her jaw when she came out to him as a teenager. Initially she sought refuge in Guatemala, but she was often beaten and discriminated against because of her gender identity.

Seoanes made her way to Mexico after someone told her that she would be more accepted there. Instead, she said, she was raped by military officials in Oaxaca. When she reported the crime, she said officials didn’t take her seriously and blamed her for “provoking” the rape.

Anderson and the interpreter told Seoanes to brace for the scrutiny.

“Just focus on your fear and what’s happened to you … that you’ve been raped and beaten and threatened with death,” Anderson told her.

“The United States is the only place where I think I will be fine being myself and not be persecuted, hurt or discriminated against,” Seoanes said. “I’ll no longer live in fear.”

Outside, Alejandra, a 25-year-old from Veracruz, tried to corral her 6-year-old daughter and 5-year-old son in the shelter’s courtyard as her boyfriend held their napping 1-year-old son.

Alejandra didn’t want to give her last name because she said her life was in danger. She said her family was on the run from her former boyfriend who had beaten her so badly he’d dislocated her collarbone.

“He’s crazy, and he has private detectives looking for me,” she said. “I’ve tried to get help in my state but he just pays off officials and nothing happens to him.”

One of the volunteers had filled out an intake form with all of Alejandra’s information. They’d made a copy and written on it in all-capital letters for her to recite, “I want a credible fear interview,” highlighting it in yellow marker.

The woman plopped down a manila folder with dozens of documents.

“I have all my proof here — police reports about how he’s beaten me,” she said.

But she was torn on whether to make the move. One of the volunteers had told her there was a good chance she’d end up in detention and her two older children — both U.S. citizens— would probably be taken away from her and placed with a family member in the U.S. or possibly in the foster care system.

Alejandra lingered for hours in the courtyard waiting for an attorney who had promised to help guide her further — possibly even taking her to the port of entry herself.

It was getting late and her two older children were cranky. They hadn’t napped all day, Alejandra explained.

Phillips assured her in Spanish: “We’ll get to you soon. I promise.”